During the time of Florence Nightingale, nursing consisted of basic nursing skills such as bathing, bed making, comfort measures, housekeeping, and positioning of the patient (Donahue, 1985; Peplau, 1988). Paplau (1988) adds during this time, the art of nursing was taught under the rubric of “nursing arts” and is commonly called “nursing procedures” (p. 8).

Following the days of Florence Nightingale, the art of nursing was being conceptualized and the science of nursing was introduced in the 1940s; although there was no application of science to practice, there was at minimum a reference made to the relationship between science and nursing (Peplau, 1988). From the 1950s to the 1970s, nursing as a science took center stage, and nursing as an art seemingly disappeared into an empirical shadow (Chinn & Kramer, 2008).

Patterson and Zderad (1977) developed a humanistic nursing model which suggested that nurses develop knowledge through both personal and aesthetic patterns. Patterson and Zderad focused on aesthetic knowledge as a way to understand the nature of being with the patient (Appleton, 1991). Their approach assisted in establishing nursing as a human science and provided the nurse with a method to attend to the lived experiences of the patient (Patterson & Zderad).

The art of nursing returned to the forefront with Barbara Carper’s (1978) Fundamental Patterns of Knowing, which emphasized esthetics as one of the four components of knowing. Carper’s work was published at a time when there was a calling to identify nursing as a unique discipline of knowledge (Boykin, Parker & Schoenhofer, 1993). Carper challenged those within the discipline to ponder the notion that nursing knowledge extended well beyond the empirical (Gramling, 2002).

Appleton (1991) derived descriptions on the artful craft of nursing from the viewpoint of both patients and nurses (Gramling, 2002). Appleton’s research utilized a phenomenological-hermeneutic-aesthetic approach which identified five distinctive meta-themes: 1) a way of being there in caring; 2) a way of being-with in understanding caring; 4) a transcendent togetherness; and 5) the context of caring (Appleton, 1991; Gramling, 2002).

Peggy Chinn (1994) published findings on the art/acts of nursing (Gramling, 2002). The results of Chinn’s study suggested, that aesthetic knowing could be shared as aesthetic criticism, whereas works of art like poetry, pictures, and stories could also be considered forms of aesthetic knowing (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). The overall purpose of Chinn’s study was to show that nurses learn through the course of imitation, reflection, varied perspectives, and communal wisdom (Gramling). Chinn believed this form of knowing provided the discipline of nursing with both appreciation and inspiration (Chinn & Kramer).

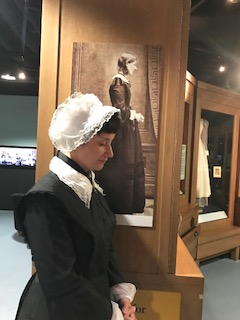

Today, the art of nursing continues to expand into the 21st century, but too few have chosen to further investigate this aesthetic practice (Gramling, 2002). Nursing continues to be introspective and caring, as the nurse continues to find new ways to interact artfully not only with their patients but with learners. Nurses use stories, poetry, music, costuming, and dance as some of the many different ways to teach, describe, and provide closure (Wendler, 2002a).

Defining the Art in Nursing

Since the Nightingale era, there have been many contributory efforts to illustrate the art of nursing, but no one definition can adequately capture every aesthetic angle (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). The art of nursing is meant to express a sensitivity that is capable of perceiving both the inner and outer beauty of the being. This beauty represents the relationship between the object and its ideal. The interaction and relationship formed between the nurse and the patient is the foundation in which the art of nursing manifests (Burke, 1992).

Rogers (2005) identified five separate senses for which nursing art can be described. Those fives senses center around the nurse’s ability to: 1) grasp meaning through encounters with the patient; 2) establish a meaningful connection with the patient; 3) skillfully perform nursing activities; 4) rationally determine an appropriate course of nursing action; and 4) morally conduct their own nursing practice (Rogers, 2005). Powers and Knapp (2006) state, “Nurses may call upon their creative, imaginative abilities to share perceptions of what is deeply meaningful about their practice experiences with others” (p. 2). Nursing is a creative discipline and an art that is directed toward caring for people (Burke, 1992). The art of nursing lies in the creative imagination and the sensitive spirit of the nurse, it is not per se in the technical, but in the background of their knowledge (Burke).

The Aesthetic Experience

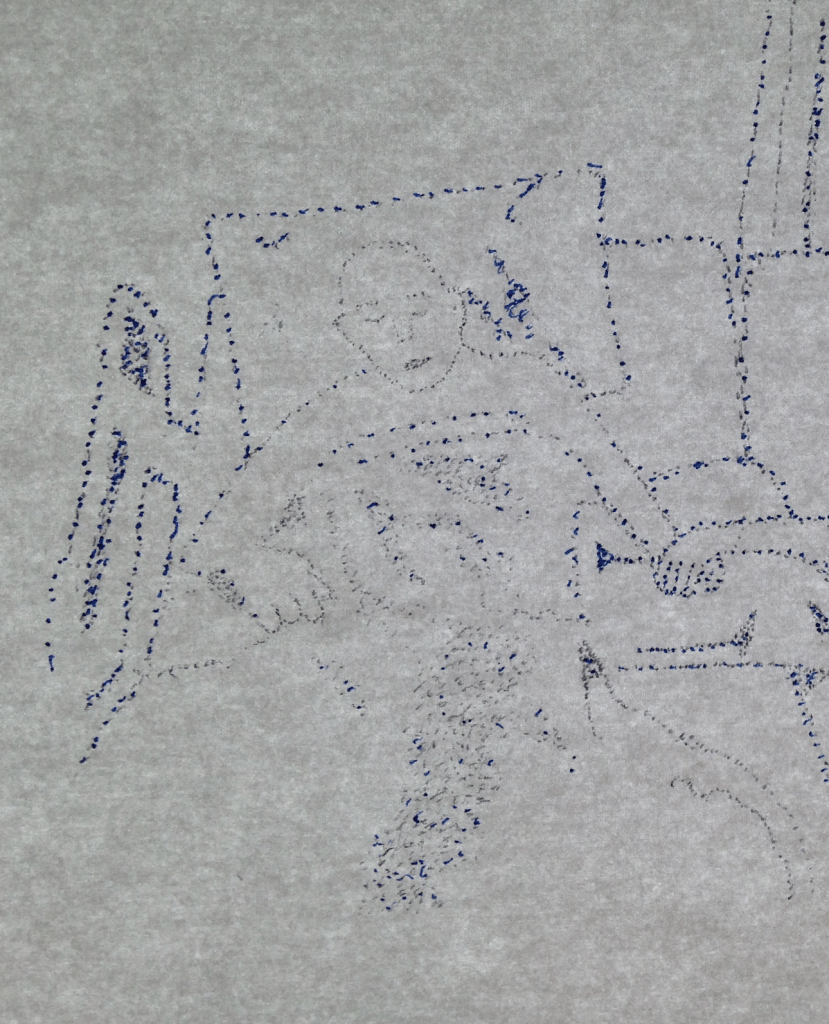

The nurse is a frequent bystander to many of life’s finest moments, unforeseen twists, and most tragic times. Aesthetic knowing involves a deep appreciation of the meaning of a situation and calls forth an inner creative understanding, which then transforms the experience (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). The following poem I wrote in the sixth grade. The accompanying picture made from a photograph as a fellow nurse helps me push my parents hospital beds together as one lives and one dies:

My thoughts are gone

My mind is blank

I see no light

I feel no strength

My heart beats ne’er more ̴

Artistic expressions such as this poem and picture represent the connectedness we have with ourselves and one another. Poetry provides a subjective expression of emotions, thoughts, and feelings which can then, in turn, be felt and experienced by others (Wendler, 2002b). The words and descriptions chosen for the poem portray the knowledge inherently learned through practice and previous experiences (Burke, 1992).

The art of nursing is the ability to come to know the patient aesthetically and through this interaction, you as the nurse appreciate the uniqueness of the situation and in turn can reflect upon the experience (Gramling, 2002). Donahue (1985) reminds us that “Nursing is not merely a technique but a process that incorporates the elements of soul, mind, and imagination. Its very essence lies in the creative imagination, the sensitive spirit, and the intelligent understanding that provides the very foundation for effective nursing care” (p. ix).

Conclusion

The nurse is unique as they have the heart and passion exhibited in artful creations and in self-expression. They possess a soulful spirit that illuminates from beyond the self and searches to capture a greater understanding in the holistic approach that combines art, research, and teaching.

Reflecting on the evidence

In A/R/Tography, the rhizome is an assemblage that moves and flows in dynamic momentum (Irwin & Springgay, 2008). It’s the “in-between space” that is constantly changing who we are, what we are, and how we proceed.

- Describe an aesthetic experience of your own.

- Produce your own definition of the art of nursing.

- Analyze your rhizome.

References

Appleton, C. (1991). The gift of self: The meaning of the art of nursing (Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. https://philpapers.org/rec/APPTGO

Boykin, A., Parker, M.E, & Schoenhofer, S.O. (1993). Aesthetic knowing grounded in an explicit conception of nursing. Nursing Science Quarterly 7(4), 158-161.

Burke, C. (1992). Pentimento praxis: Weaving aesthetic experience to evolve the caring beings in nursing (Doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=5776793

Carper, B. A. (1999). Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. In E. C. Polifroni & M. Welch (Eds.), Perspectives on philosophy of science in nursing (pp. 12-19). Lippincott.

Chinn, P.L. & Kramer, M.K. (2008). Integrated theory and knowledge development in nursing. Elsevier.

Donahue, P.M. (1985). Nursing the finest art: An illustrated history. Mosby.

Gramling, K.L. (2002). When is nursing art? In M.C. Wendler (Ed.), The heart of nursing (pp. 3-13). Sigma Theta Tau International.

Rieger, K. & Chernomas, W. (2013). Arts-Based Learning: Analysis of the Concept for Nursing Education. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 10(1), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijnes-2012-0034

Irwin, R.L. & Springgay, S. (2008). A/R/Tograhphy as practice-based research. In S. Springgay, R.L. Irwin, C.; Leggo, & P. Gouzouasis (Eds.) Being with A/R/Tograhpy. SensePublishers.

Parse, R.R. (1988). Beginnings. Nursing Science Quarterly 1(1), p 1-2.

Paterson, J. G., & Zderad, L. T. (1976). Humanistic nursing. National League for Nursing.

Peplau, H.E. (1988). The art and science of nursing: similarities, differences, and relations. Nursing Science Quarterly 1(1), 8-15.

Powers, B.A. & Knapp, T.R. (2006). Dictionary of nursing theory and research. Springer Publishing Company.

Rodgers, B. L. (2005). Developing nursing knowledge: Philosophical traditions and influences. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Wendler, M. C. (2002a). The healing power of art. In M.C. Wendler (Ed), The heart of nursing (pp. 115-116). Sigma Theta Tau International.

Wendler, M.C. (2002b). The heart of nursing: origins. In M.C. Wendler (Ed), The heart of nursing (pp. 1-2). Sigma Theta Tau International.

Dedication

Martha R. Alligood, Ph.D., RN, ANEF, for helping me understand the value of theory without judgment after I told her “I don’t know if we really need theory to practice nursing”. Fast-forward a few years, Dr. Alligood wasn’t surprised to find out I was teaching theory ; )

Special Thanks

To my London family-oodles of love. My sincere apologies, I forgot the name of my photographer! (email me let’s catch up!)

Pingback: Filled with the Light – Time Traveling Nurse

Pingback: PreBrief or DeBrief: The Art Story – Time Traveling Nurse